https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20181016-how-lsd-influenced-western-culture

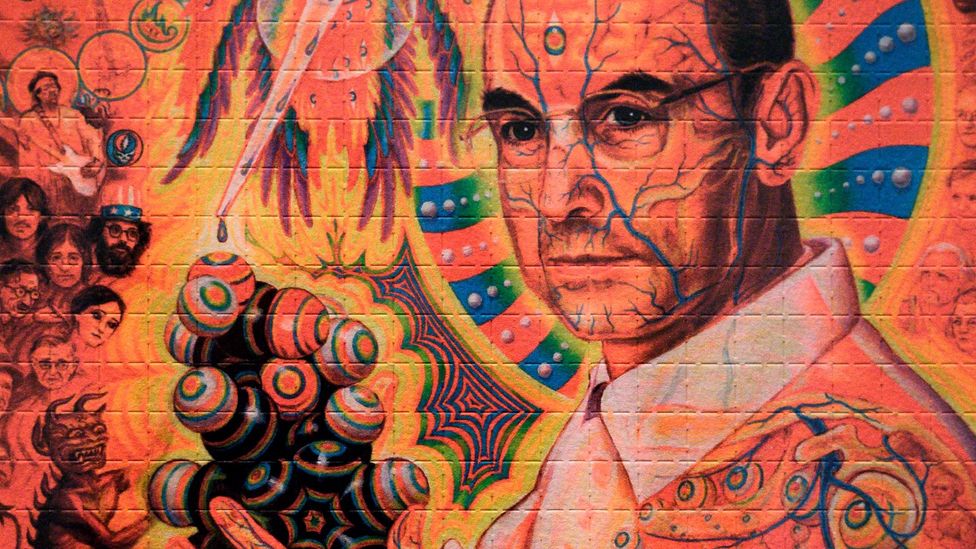

How LSD influenced Western culture (Image credit: Getty)

By Holly Williams17th October 2018A new play, All You Need is LSD, tracks the importance of psychedelic drugs beyond just flower power. Is it time for a third ‘summer of love’?W

When you think of LSD, a very specific aesthetic probably leaps to mind: the psychedelic pink-and-orange swirls of the 60s; naked people with flowers in their hair; the shimmer of a sitar. After its psychedelic properties were accidentally discovered in the lab by Albert Hofmann in 1943, the drug was banned in the UK in 1966. LSD is still most strongly associated with hippies who embraced its mind-expanding properties.

In fact, the drug’s after-effects have seeped through much of Western culture, from art to literature to, most obviously, music, which was never the same after Bob Dylan, The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix dropped acid. Whole genres have since flagged their debt to mind-altering substances: psychedelic rock, psytrance, acid house… the latter hailing from that other spike in psych: 80s and 90s rave culture. Although ecstasy is the drug most associated with the second summer of love, LSD also saw a resurgence in the UK at that time.

– Why Yellow Submarine is a trippy cult classic

– The strange power of the ‘evil eye’

– The LSD cult that transformed America

That was 30 years ago. Are we due another psychedelic renaissance? British playwright Leo Butler hopes so. “There was a need – political, socially – for that LSD explosion in the 60s and the ecstasy explosion in the early 90s,” he tells BBC Culture. “You look at the world now and think, god it could really do with a super-strong psychedelic! We need something to bring us together – let’s have a third summer of love.”

A portrait of Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman, who accidentally discovered LSD’s psychedelic properties in 1943 (Credit: Getty)

Having experimented with drugs when he was younger, Butler wanted to write an honest view of the psychedelic experience. But he also wanted to acknowledge the influence of LSD beyond just flower power – and his new show All You Need is LSD brings us right up to the present moment.

In recent years, LSD has undergone something of a public image shift, from Steve Jobs talking about his experiences to Silicon Valley types advocating microdosing (taking tiny amounts of the drug to boost creativity). The first placebo-controlled study into microdosing was launched in September by the Beckley Foundation and Imperial College London, while the UK has also conducted medical trials that investigate LSD’s potential therapeutic uses.

While it may not quite be a summer of love, it might just be the beginning of a new era of openness, even respectability, for the drug.

Mood music

This medical interest even found its way into Butler’s play. In 2015, he interviewed former UK government drugs tsar Professor David Nutt, who mentioned he was about to begin the first medical trial on LSD in 50 years. That Tuesday. Would Butler like to take part?

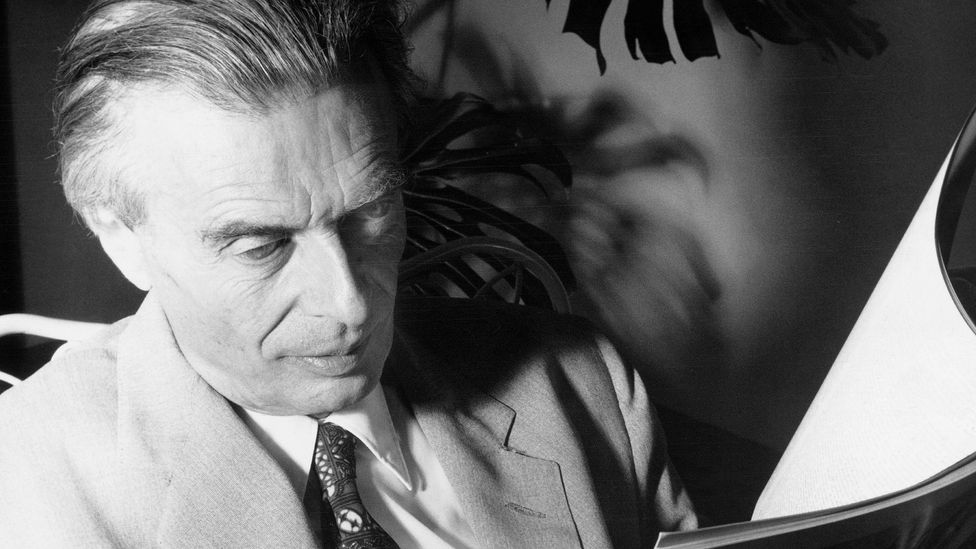

Several artists, writers and musicians are known to have indulged in LSD, including the English writer Aldous Huxley (Credit: Getty)

This incredibly good timing changed the play: All You Need is LSD now stages Butler’s medically monitored trip. Which in turn allows him to freely hop about in space and time, and to surreally introduce key figures from the drug’s history (Hofmann, Timothy Leary) and artists who’ve been known to indulge, from Aldous Huxley to Miles Davis to Helen Mirren.

It’s only really in music that there’s a true overlap between work made about acid, and work made for enjoying when on acid

“I had to have The Beatles, but I’d like to have The Monkees and Dylan in there too,” says Butler, a little wistful about potential talking heads he just didn’t have room for. “It would’ve been great to go into the 70s and have The Velvet Underground, Andy Warhol, David Bowie… and I wanted the Madchester stuff – the Happy Mondays and The Stone Roses.”

Lots of musicians – no surprises there. Because LSD’s most obvious and pervasive influence on culture is to be found in music. That’s surely because music can be enhanced by the drug, prompting synaesthetic responses: seeing sounds as colours, patterns, shapes. What LSD doesn’t do, however, is make it easy to read a book, or concentrate on plot. So it’s only really in music that there’s a true overlap between work made about acid, and work made for enjoying when on acid…

The Beatles posing with cardboard cut-outs of their Yellow Submarine characters in 1967 – its trippy visual style reflected the height of the psychedelic era (Credit: Getty)

And it didn’t hurt that proper superstars were into it: The Beatles, Brian Wilson, Pink Floyd… their influence is huge, and frankly unavoidable. Few musicians working today could claim to be unaffected by records such as, say, Revolver. The Beatles’ ‘acid album’ was released in 1966, and was a huge leap forward in sound, featuring tape looping, reversed guitars, vocal effects and altered speeds. The warp and wobble of Tomorrow Never Knows – with lyrics based on Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience Manual – might sound a bit trippy-hippie cliche today, but it was revolutionary at the time.

And while the sonic experimentation prompted by LSD may have rippled right into mainstream pop music, it’s not like full-on psych has ever really ceased: you can see it noodling away, right up to today’s bands such as The Flaming Lips, Ariel Pink, Connan Mockasin, and Tame Impala.

But what about other art forms? Is there a great LSD play?

“Part of the reason I wanted to write this was I didn’t think there had been, really,” says Butler. “But I suppose in the 60s there was Hair.” The musical, about long-locked hippies, was upfront about drugs (and nudity), opening in the West End in 1968, the day after the abolition of stage censorship in the UK. And this was part of a general opening up of culture and a flourishing of experimentation in form.

Leo Butler’s new show All You Need is LSD explores the influence of the drug on culture (Credit: All You Need is LSD)

“Writers and theatres could be much more free – it was the time of the Royal Court and Theatre Workshop,” suggests Butler. “Even if you wouldn’t think of someone like Edward Bond or even Pinter with LSD there is something about questioning how a play is made, what is the audience experience, that is very counter-cultural. Caryl Churchill is a wonderfully psychedelic writer. Does she indulge? Probably not. But there’s something in the work.”

He points, too, to the explosion of inventive work in the 1990s – in-yer-face theatre makers such as Sarah Kane and Mark Ravenhill. “They were the children of the 80s’ summer of love. That rebellion is there not just in what they were saying, but in the form of their plays.”

Infinite spaces

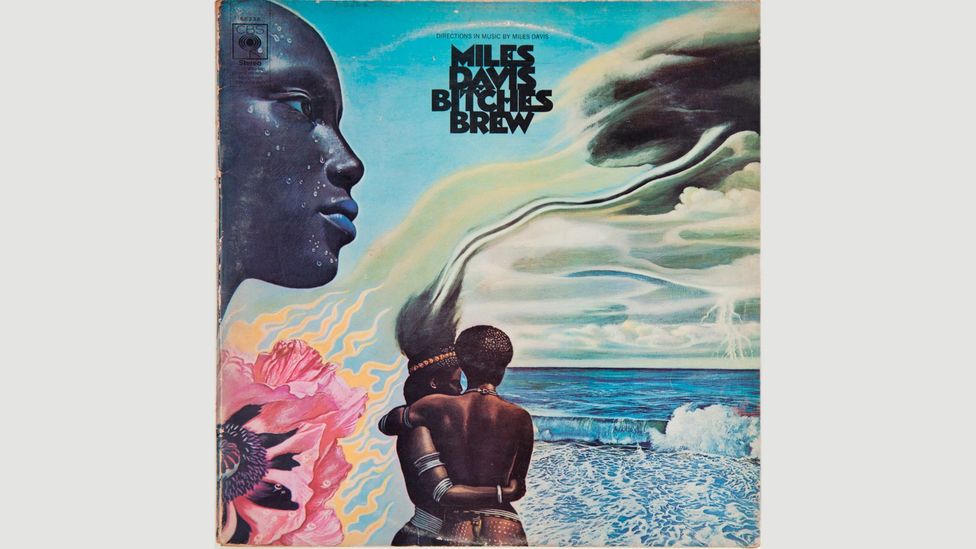

Unlike theatre, in visual art the iconography of LSD is very clear. And there is overlap with music: the really classic psychedelic imagery is found on record sleeves and posters. Think of painter Mati Klarwein, who did Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew cover, and Martin Sharp, who created Cream’s Disraeli Gears, or design collectives such as Hipgnosis – Pink Floyd sleeves – or The Fool – Incredible String Band record covers and costumes for The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour. Wes Wilson, Victor Moscoso and Bonnie MacLean all helped define the look of the era in San Francisco with their influential posters.

Mati Klarwein painted Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew cover, one example of the classic psychedelic imagery found on record sleeves and posters (Credit: Alamy)

What’s fascinating in art is how influence seems to stretch back as well as forward; there’s an obvious drawing on the swirling style of Art Nouveau and Jugendstil, as well as from the wilder experiments of Surrealism. What could be more trippy than time itself melting in Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory? You could argue that the visuals acid unlocked have always been lurking in our subconscious. Well, a Surrealist would, anyway.

The psychedelia of the 60s now looks utterly of its moment – making LSD almost a “victim of its own iconography”, Butler says. Yet hallucinogenic experiences continue to appeal to artists, and many have since played with those druggy tropes, albeit sometimes in a knowing or satirical fashion.

After experimenting with hallucinogens, German artist Sigmar Polke kitschily referenced them in the 1970s, painting red-and-white mushrooms and co-opting the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland. Indeed, Lewis Carroll’s children’s story has apparently endless appeal for the creative adult caner: it’s referenced endlessly, from Jefferson Airplane’ song White Rabbit to Adrian Piper’s Alice screenprints, and even features in Butler’s new play.

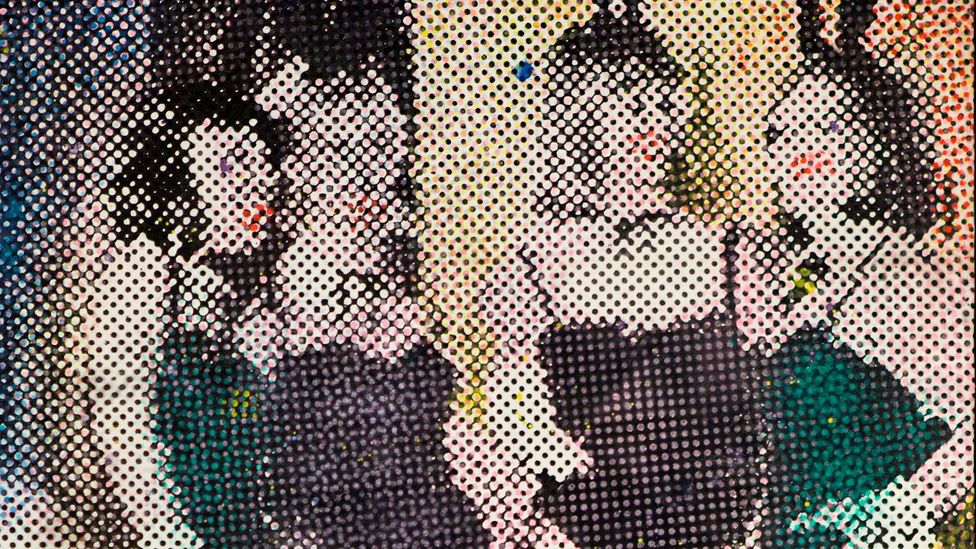

German artist Sigmar Polke, whose work includes Bunnies, painted red-and-white mushrooms and the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland after experimenting with LSD (Credit: Alamy)

Yayoi Kusama also did a version of Alice – and the Japanese artist has certainly found a way to make psychedelia resonate with Millennials. Disorientating dots, infinite spaces, swirly mushrooms and neon flowers… her take on psychedelia has made her one of the most popular (read: Instagrammable) living artists.

Kusama often creates 360-degree, all-encompassing sensory experiences through installations – and an immersive approach that is popular when crafting high art. See also Carsten Holler’s Upside Down Mushroom Room (2000), the ceiling hung with oversized rotating fly agarics, or Kenny Scharf’s fluorescent ‘Cosmic Caverns’ of day-glo junk. The US artist has been making them since the 1980s, when he first decorated a cupboard he would take a weekly mushroom trip in.

Carsten Holler’s Upside Down Mushroom Room, 2000, has a ceiling hung with agarics (Credit: Getty)

And in the 90s, the edgy wave of Young British Artists also found a creative (and lucrative) overlap between mind-altering substances and art, counter-culture meeting consumer culture nicely. Damien Hirst named his dot paintings after drugs, after all – one is titled LSD – and filled a medicine cabinet with pretty pills.

Easy riders, acid tests

Film-makers have long explored cinema’s potential for creating dream-like experiences: so swift was the establishing of the narrative ‘rules’ of cinema, through the grammar of shot reverse shot, that as early as 1929 the Surrealist Luis Buñuel was able to seriously unsettle viewers simply by breaking them. Cinema’s capacity to unnerve, to distort apparent reality, has been manipulated by directors ever since, from Alejandro Jodorowsky to David Lynch to Leos Carax.

Peter Fonda, Jack Nicholson and Dennis Hopper starred in Easy Rider, which featured an acid trip and a shoot that was awash with drugs (Credit: Getty)

At the height of the 60s’ psychedelic era, its specific visual style also flourished in movies. Again, this was often linked to music: consider cheerily surreal romps like The Monkees’ Head and The Beatles’ animation Yellow Submarine.

Bright colours, wavy special effects, blurry distortion, jump cuts… the cinematographer’s craft for signalling high-as-hell on celluloid quickly became its own cliché

Various films explicitly sought to recreate the acid experience, such the kaleidoscopic The Trip (banned by film censors in the UK) and Psych-Out. Jack Nicholson wrote the former and starred in the latter, and also cropped up in Easy Rider with Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda. A road-trip movie that features an acid trip, the infamous shoot actually was awash with drugs.

Bright colours, wavy special effects, blurry distortion, jump cuts… the cinematographer’s craft for signalling high-as-hell on celluloid quickly became its own cliche. But, as with art and music, some modern directors continue to develop the psychedelic style. Most obviously, Gaspar Noé, who dubbed his 2009 film Enter the Void a “psychedelic melodrama” (it was loosely based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead – itself the basis for Leary’s The Psychedelic Experience). Its rapid flashing lights and neon colours wigged viewers out, but divided critics.

Gaspar Noé has continued to develop the psychedelic style with films such as Enter the Void (2009) (Credit: Alamy)

His latest, Climax – apparently based on a true story about a 90s dance troupe who had a mass freak-out after being spiked with, yup, LSD – was released last month, and has proved similarly dizzying.

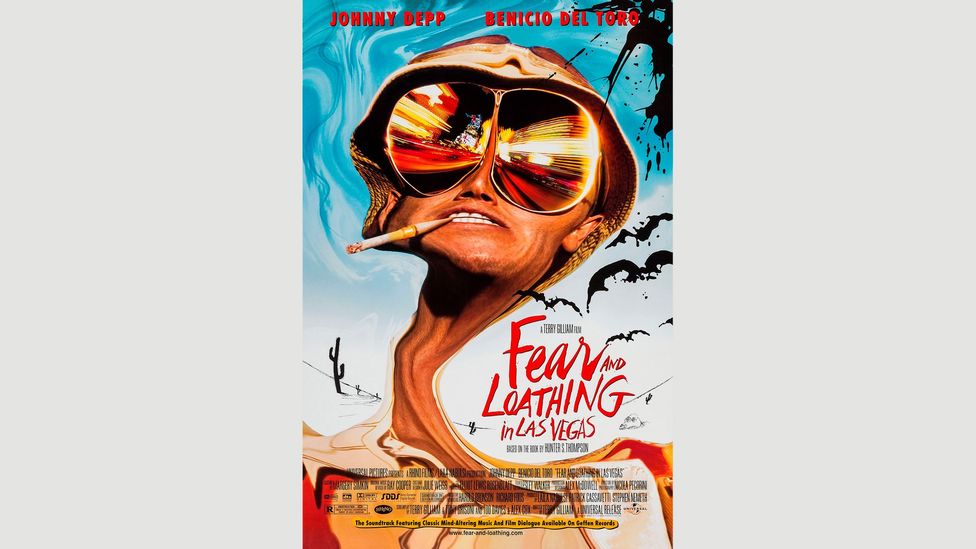

Without the sensory assault of cinema, literature appears to struggle more to evoke altered states – so perhaps it is no wonder that when it works, it often translates well to screen too. Hunter S Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas – and it film adaptation directed by Terry Gilliam – have become cult classics, fans often praising just how accurately they capture the experience of tripping your head off (those carpet patterns climbing the walls, man).

Hunter S Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas – and the 1998 film adaptation by Terry Gilliam – have become cult classics (Credit: Alamy)

More non-fiction or philosophical tomes (Ram Dass’ Be Here Now, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, much of Leary) have been written about LSD than fictionalisations – although Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, about novelist Ken Kesey and his group of ‘Merry Pranksters’ who journeyed across the US taking a shedload of LSD, famously blurred the boundaries. A hugely influential example of ‘New Journalism’, it did nothing less than change the way we think about how the truth can best be told.

And that’s the thing about how culture has been affected by the drug: to convey new experiences, it was also often necessary to come up with new forms. And such inventions then changed culture, even for those who’d never touch the stuff.

“Sometimes LSD’s influence is explicit, other times I think it’s the ripple effect on the culture,” Butler explains. It might be tempting to write off psychedelia as just a load of swirly stuff – but in fact, we can all still feel those ripples.

All You Need is LSD is on tour in the UK till 17 November

Posted on November 12, 2021

0